Highly effective and safe vaccines are available to prevent HBV and HPV infections and associated cancers.

An estimated 257 million people are living with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection globally. HBV is responsible for nearly 900,000 deaths annually, including more than 300,000 deaths from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HCC results from chronic HBV infection, and the risk of chronic infection is greatest if transmission occurs during birth or early childhood. The vaccines for HBV have been available since 1982 as a three-dose series, and can prevent chronic infection and sequelae including cirrhosis and HCC. As of 2017, 186 countries had introduced HBV vaccination, and globally 3-dose vaccination coverage among children reached 84%. (Map 1) To prevent mother-to-child transmission, the first dose should be given within 24 hours after birth; however, only 101 countries (55%) had introduced universal HBV vaccine birth dose, and coverage globally was estimated at 43%.

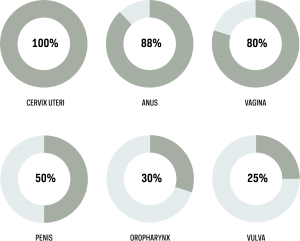

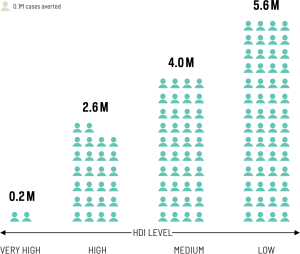

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the cause of 630,000 cancers annually, 83% of which are cervical cancers, 10.9% other anogenital, and 4.6% oropharyngeal cancers. (Figure 1) Two HPV vaccines, a bivalent and a quadrivalent vaccine, have been available since 2006. A third vaccine, a nonavalent vaccine, has been available since 2015. These vaccines, combined with screening, have the potential to avert millions of cervical cancer deaths over the coming decades. (Figure 2)

Figure 1. Cancers associated with HPV and percent of cases attributable to HPV infection. 100% of cervix uteri cancer cases are attributable to HPV; 885 of anus cancer cases; 80% of vagina cancer cases; 50% of penis cancer cases; 30% of oropharynx cancer cases; and 25% of vulva cancer cases.

Figure 2. Cervical cancer cases averted (millions) in 2020–2069 with implementation of screening twice per lifetime and 80–100% female-only vaccine coverage with nonavalent HPV vaccine, by Human Development Index level (HDI). 0.2 million cervical cancer cases would be averted in very high HDI countries.

2.6 million cervical cancer cases would be averted in high HDI countries.

4.0 million cervical cancer cases would be averted in medium HDI countries.

5.6 million cervical cancer cases would be averted in low HDI countries.

They are given as a three-dose or a two-dose series, are highly effective and safe, and target HPV types 16 and 18 (which cause over 70% of all cervical cancers) and most other cancers that are caused by HPV. The nonavalent vaccine targets HPV types 16 and 18 as well as five additional cancer-causing HPV types; these seven types cause over 90% of cervical cancers. In most countries, the target group for HPV vaccination is young adolescent girls; some countries also recommend vaccination for boys. The first countries to introduce HPV vaccine were high-income countries, due to the cost of vaccines. Middle- and low-income countries started to introduce vaccines three to six years later. By 2019, over 96 countries had introduced HPV vaccination. (Map 2)

ACCESS CREATES PROGRESS

Rwanda has some of the highest cervical cancer rates in the world. However, this country has achieved greater than 98% coverage in its HPV vaccine target population due to government commitment, school-based delivery, and a strategy to reach out-of-school girls.

Liver cancer rates in Taiwan and China:

Chiang CJ, Yang YW, You SL, Lai MS, Chen CJ. Thirty-year outcomes of the national hepatitis B immunization program in Taiwan. JAMA. 2013;310(9):974–976.

Access creates progress:

Black E, Richmond R. Prevention of Cervical Cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Advantages and Challenges of HPV Vaccination. Vaccines. 2018;6(3):61.

Text:

de Martel C, Plummer M, Vignat J, Franceschi S. Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and HPV type. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:664–670.

Gallagher KE, LaMontagne DS, Watson-Jones D. Status of HPV vaccine introduction and barriers to country uptake. Vaccine. 2018;36:4761–4767.

Li X, Dumolard L, Patel M, et al. Implementation of hepatitis B birth dose vaccination- worldwide, 2016. Weekly Epidemiologic Record. 2018;93:61–72.

World Health Organization. Global and Regional Immunization Profile: Data as of 21 September 2018. Accessed at: http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/gs_gloprofile.pdf?ua=1

World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/255016. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

World Health Organization. Hepatitis B vaccines: WHO position paper- July 2017. Weekly Epidemiologic Record: 2017;27:369–392

Map 1:

World Health Organization Global Health Observatory Data, https://www.who.int/gho/en/

Map 2:

World Health Organization Immunization, Vaccines, and Biologicals Database, https://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/en/

Figure 1:

de Martel C., Plummer M, Vignat J, et al. Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and HPV type. International Journal of Cancer. 2017;141(4):664–670.

Figure 2:

Simms KT, Steinberg J, Caruana M, Franceschi S. Impact of scaled up human papillomavirus vaccination and cervical screening and the potential for global elimination of cervical cancer in 181 countries, 2020–99: a modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(3):394–407.