Universal Health Coverage

Universal health coverage improves cancer outcomes equitably and promotes financial protection as well.

Universal health coverage (UHC) means that all people have access to the healthcare services they need, and that the services are of high quality without resulting in financial hardship for patients and their families. UHC has become an important policy goal in many countries, and plays a key role in the health-related United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

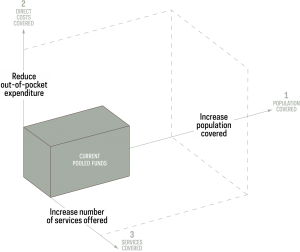

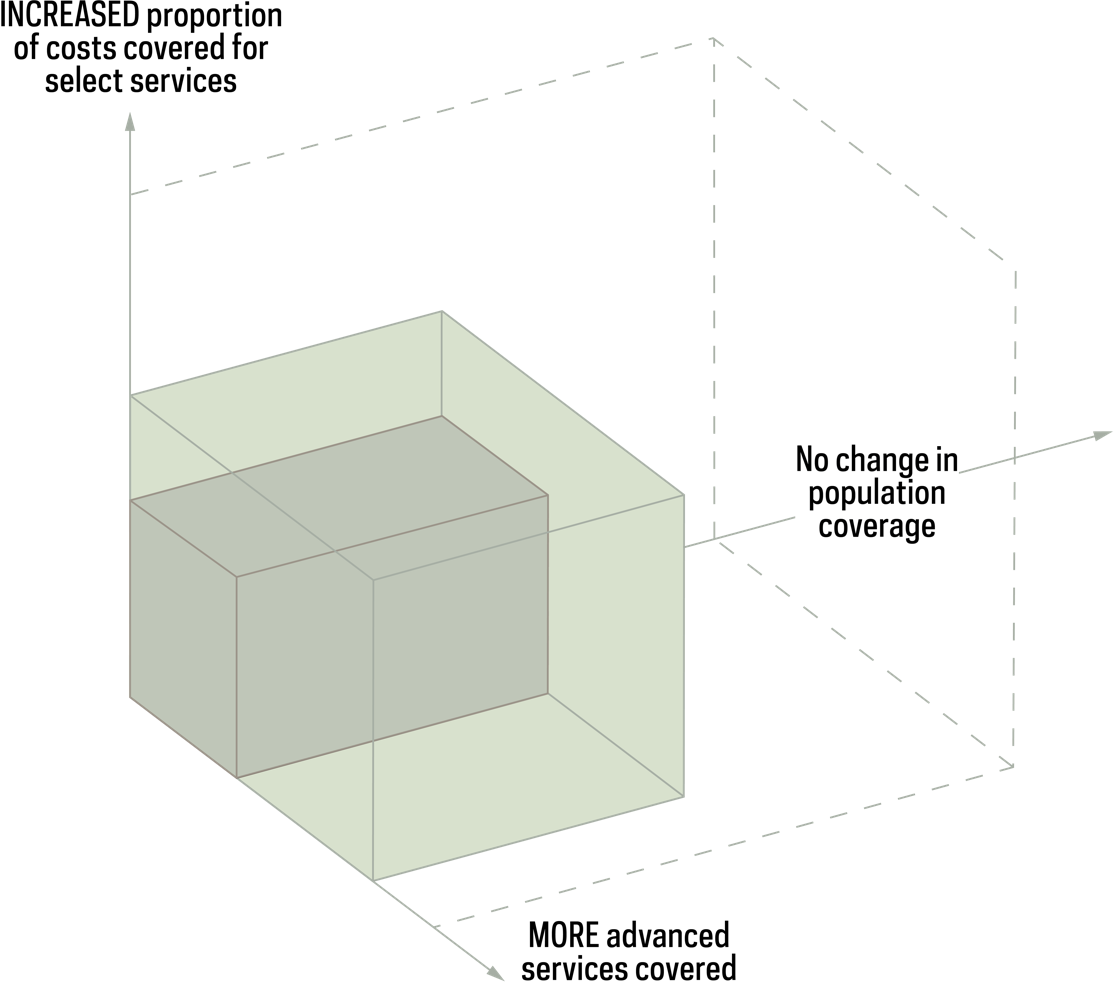

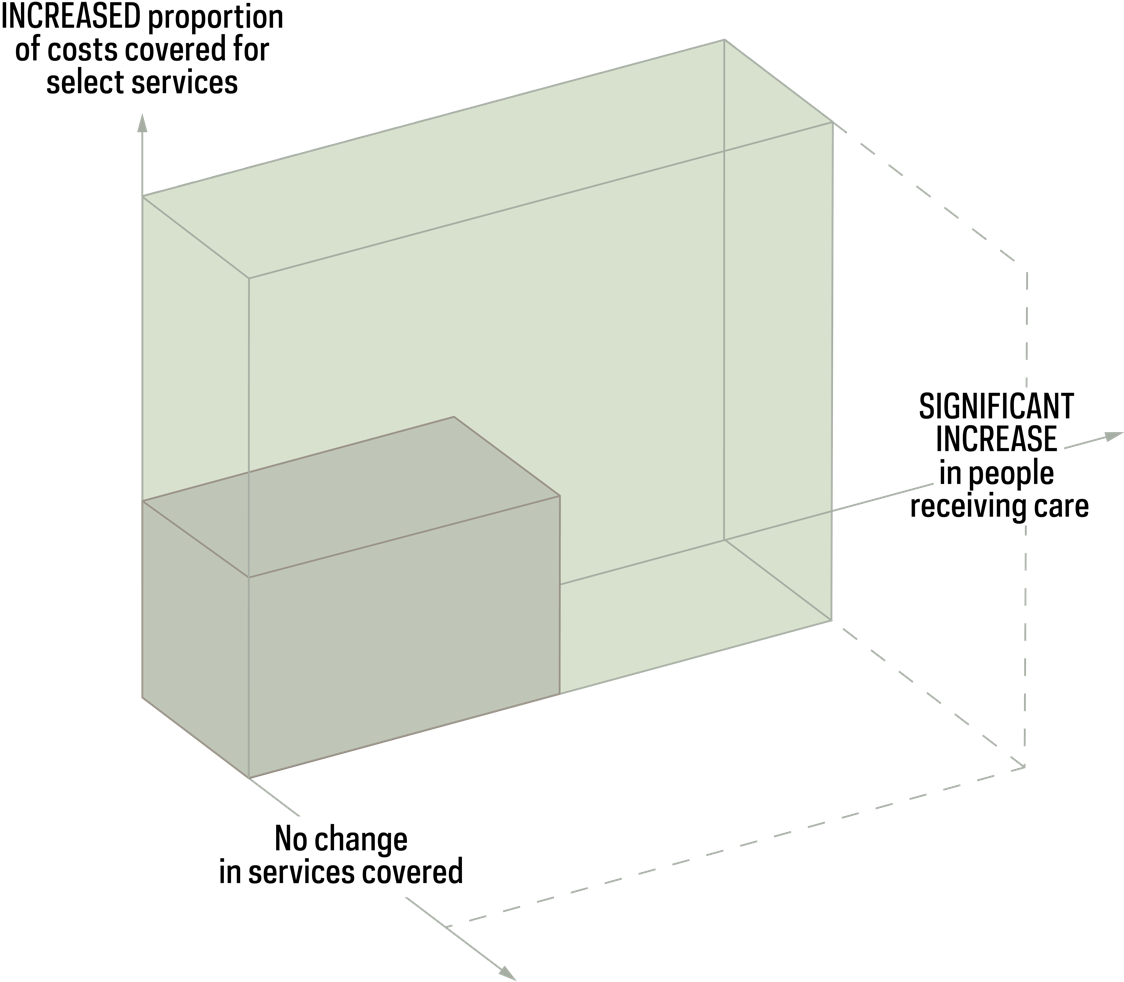

Countries should progress towards UHC through a process of progressive realization by moving sequentially along 3 dimensions: (1) increase the proportion of the population covered; (2) increase the proportion of prepaid funds and reduce out-of-pocket payments; and (3) expand the number of services available to the population. (Figure 1) As a starting point, the most effective way to improve cancer outcomes and achieve greater equity is to maximize the number of individuals who have access to effective services while ensuring financial protection before introducing new services. (Figure 2)

Considerations for progressing towards universal health coverage. A three-dimensional box labeled “current pooled funds” lies in the center of three axes labeled as follows: 1. Population covered: increase population covered 2. Direct costs covered: reduce out-of-pocket expenditure 3. Services covered: increase number of services offered

Figure 2. The universal healthcare coverage approach to cancer care. First image: Advanced services approach to cancer care. Two three-dimensional boxes, one smaller and within the larger, lie in the center of three axes. The larger box is about 50% larger than the smaller, and is similarly larger in each of the three directions of the axes. The axes are labeled as follows: More advanced services covered; no change in population coverage; and increased proportion of costs covered for select services. Introducing advanced services, such as screening or targeted therapies, available only to select populations results in minor improvements in population outcomes. Second image: UHC approach to cancer care. Two three-dimensional boxes, one smaller and within the larger, lie in the center of three axes. The larger box is about 3 times as large as the smaller, and is larger in the directions of two of the axes. The axes are labeled as follows: No change in services covered; significant increase in people receiving care; increased proportion of costs covered for select services. Expanding core services, such as pathology and basic treatment, to entire population and ensuring financial protection of such results in a major improvement in population outcomes.

Governments provide a pre-specified set of services to a distinct population using a pool of funds as part of a “benefits package.” However, comprehensive cancer services are not covered in the majority of countries, and effective health promotion, prevention, early detection, treatment, and palliative and survivorship care are frequently unavailable. (Figure 3)

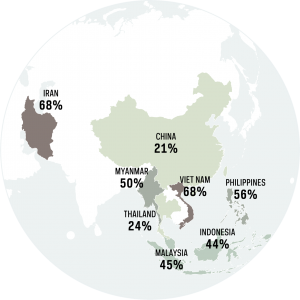

For individuals diagnosed with cancer, high out-of-pocket payments and the indirect costs of treatment often result in financial hardship, impoverishment, loss of income due to limitations in or inability to work, and worsened health for that individual and their family. (Figure 4) To realize UHC, cancer services must be included in benefit packages and sustainably financed through domestic public resources, and cancer patients must be protected against financial ruin.Figure 4. The percentage of the cancer population who pays more than 30% of total household income for healthcare costs, select countries in Asia. In China, 21% of the population pays more than 30% of total household income for healthcare costs. In Iran, 68% of the population pays more than 30% of total household income for healthcare costs. In Myanmar, 50% of the population pays more than 30% of total household income for healthcare costs. In Thailand, 24% of the population pays more than 30% of total household income for healthcare costs. In Viet Nam, 68% of the population pays more than 30% of total household income for healthcare costs. In Malaysia, 45% of the population pays more than 30% of total household income for healthcare costs. In the Philippines, 56% of the population pays more than 30% of total household income for healthcare costs. In Indonesia, 44% of the population pays more than 30% of total household income for healthcare costs.

ACCESS CREATES PROGRESS

The creation of Seguro Popular in Mexico, making universal health coverage mandatory through a system of social protection, has improved access to care and survival from breast and childhood cancers.

Each country may utilize a different approach to attain UHC. Yet, there are critical implementation principles. First, multi-sectoral dialogue is important to set priorities and define a health benefits package based on health needs, health system capacity, budget envelope, equity, and other guiding principles. Second, investing in health system capacity and equitable models for delivering services promotes access, particularly for vulnerable communities. Finally, utilizing sustainable financing mechanisms based on public and compulsory funding sources ensures financial protection. By including comprehensive cancer services as part of UHC, countries can achieve better overall outcomes, more efficiently and with greater equity.

Achieving UHC is not quick or easy. It takes time, and it takes sustained political will, and community participation and ownership. But UHC is not something you achieve once. It must be constantly sustained.

Quote:

Ghebreyesus TA. Achieving universal health coverage: from the past to the future. Prince Mahidol Award Conference, Bangkok, Thailand. 2 Feb 2018. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/achieving-universal-health-coverage-from-the-past-to-the-future-prince-mahidol-award-conference-bangkok-thailand

Text:

Jan S, Laba TL, Essue BM, et al. Action to address the household economic burden of non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 2018 May 19;391(10134):2047–2058.

Meheus F, Atun R, Ilbawi A. The Role of Health Systems in Addressing Inequalities in Access to Cancer Control. In: IARC Social inequalities and cancer. 2019.

Watkins D, Jamison D, Mills A, Atun R, Danforth K. Universal health coverage and essential packages of care. In: Jamison D, Gelband H, Horton S, Jha P, Laxminarayan R. (eds.), Disease Control Priorities (third edition): Volume 9, Disease Control Priorities. Washington, DC: World Bank. 2017.

World Health Organization. Assessing national capacity for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: global survey. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/276609/9789241514781-eng.pdf.

Figure 1:

World Health Organization. Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage. Final report of the WHO Consultative Group on Equity and Universal Health Coverage. 2014. https://www.who.int/choice/documents/making_fair_choices/en/

Figure 2:

Original figure by authors.

Figure 3:

Assessing national capacity for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: global survey. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/276609/9789241514781-eng.pdf

Figure 4:

With the exception of the following:

China: >40% of total household income

Iran: >40% of capacity to pay (household income remaining after basic needs have been met)

Jan S, Laba TL, Essue BM, et al. Action to address the household economic burden of non-communicable diseases. Lancet. 2018 May 19;391(10134):2047–2058.

Explore Related Topics

This figure cannot be displayed at mobile resolutions.

To view this figure, please visit the desktop version of this website or download the PDF file of the book chapter.